Your teeth are important. And I don’t just mean right now. They’ll continue to be important long after… well, you know.

And it may sound odd, but your teeth can help future generations understand how we lived, what we ate, the work we did, and even how we moved around as a people.

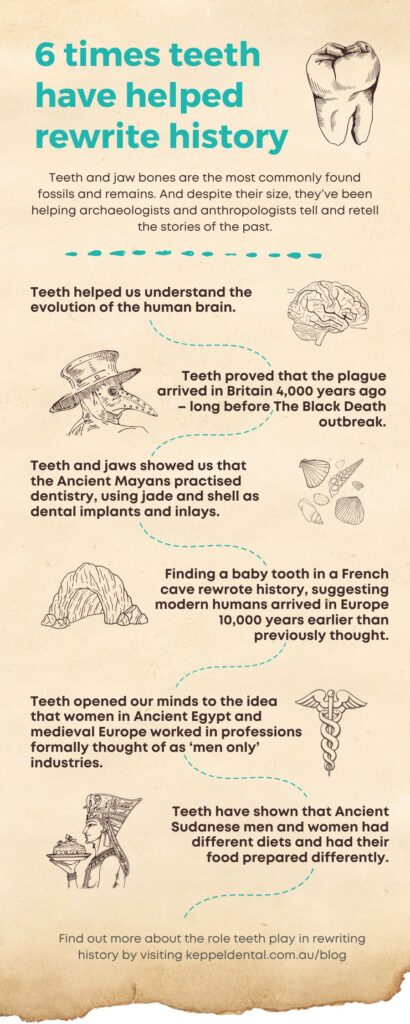

That’s because teeth and jawbones are the most commonly found fossils. They’re found more often than skulls and other bones. The tough enamel that covers teeth (along with their calcium properties) helps them stand the test of time. And so archaeologists and anthropologists rely on them to piece together the stories of our ancestors.

Fossilised and well-preserved teeth have helped historians better understand human evolution, early migration, health practices, early dentistry, and even the roles of men and women. What they discover sometimes challenges what we previously assumed about people of the past.

6 times teeth have helped rewrite history

I’m a modern dentist who absolutely nerds out over the latest industry technologies and what the future holds (such as AI dentistry). But it’s also fascinating to understand how these little bits of bone and calcium can tell us so much about the past. And with the development of non-invasive virtual anthropology, it’s fascinating to see the old and the modern world collide.

With that said, here are just 6 tooth-led discoveries that have made us rethink the lives of people from civilisations that are long gone.

1. The evolution of pregnancy

Birth. It’s hard, messy, painful and exhausting. (Or so I’m told.) Humans definitely haven’t evolved to make this part of the lifecycle effortless. In fact, evidence suggests the opposite may be true: the smarter we got, the harder we made it for ourselves.

What’s been found: It took 6 million years for the size of the prenatal human skull and brain to increase, arriving at the current human-like gestational growth rates about half a million to a million years ago. And this increase in brain size correlates with when our human ancestors started using more tools. As we got smarter our brains grew. And as we developed in the womb our heads got bigger.

Who made the finding: Western Washington University paleoanthropologist Tesla Monson.

How teeth helped: Permanent adult teeth develop in the second trimester. Using data collected from fossilised molars and skill fragments of primates that lived from 6 million to 12,000 years ago, Monson and her colleagues compared the changes in proportions over time. This helped them track the prenatal growth rate of the brain, and identify when evolutionary changes in the size of the head and brain actually happened.

Read more about it: Teeth tell the story

2. When the plague arrived in Britain

Britain’s worst outbreak of the Bubonic Plague was in 1348. But the bacteria responsible for The Black Death made its way to the island long before that.

What’s been found: Two children aged between 10 and 12, and one woman aged between 35 and 40, proved the plague was present in Britain long before 1348. The cases date back 4,000 years. And while it wasn’t the cause of their deaths, all three people were carrying Yersinia pestis – the bacteria responsible for the plague.

The discovery was made in 2023. And up to that point this strain of plague bacteria was only evident in Eurasia. This new finding helps researchers better understand the movement of infectious diseases between people, and how this strain of Yersinia pestis could pass from person to person without the help of fleas.

Who made the finding: Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute, working with the University of Oxford and local history and museum groups.

How teeth helped: DNA can be trapped inside the dental pulp within a tooth. By drilling into the teeth and extracting some of the pulp, they were able to analyse it and identify the plague bacteria.

Read more about it: 4,000-year-old plague DNA found

3. Dental implants aren’t a new idea

If you lose a tooth today, it can be replaced with a dental implant made of titanium capped with a strong zirconia crown.

However, these materials only came into use in the 1970s and 2010s respectively. But teeth were being replaced with something synthetic long before then.

What’s been found: Evidence was discovered showing pre-Mayan tribesmen were replacing missing teeth with jade, stone or shell. And while the materials are a bit rough and ready by today’s standards, astoundingly there’s evidence of the jaw bone fusing to the implant—something that’s still part of the treatment process today.

Archaeology teams have also found evidence of tooth inlays. Ancient Mayan dentists fixed precious stones such as jade to teeth by expertly drilling a hole into the tooth and securing them using a super-strong, plant-based adhesive. (So strong that it could last 4,000 years.)

Originally, it was presumed that only high-standing members of society would have these inlays. But further research found this wasn’t the case. People considered poor also showed signs of undergoing the treatment. The current thinking is that the jade inlays were used to repair tooth decay. Analysis of the adhesive shows it included medicinal plants that reduce inflammation and fight infection.

Who made the findings: Dr Colvard at the University of Illinois in Chicago, and Gloria Hernandez-Bolio from Cinvestav in Mexico.

How teeth helped: Teeth were at the root of these studies, and were looked at using CT analysis and x-rays. Researchers got a better view of how the implants and inlays were fixed to the teeth, what they were made of, and what organic ingredients were used.

Read more about it: What ancient teeth can tell us about humanity’s past and Ancient Maya practice of gluing gemstones onto teeth may have been for more than bling.

4. Challenging what’s known about early migration

Getting around wasn’t always as easy as hopping into the car or catching a plane. So significant movement of ancient people across continents, and understanding why or how they got there, is a big deal.

What’s been found: A baby tooth found in a cave in France suggests that modern humans arrived in Western Europe 10,000 years earlier than originally thought. What’s also interesting is the evidence of Neanderthals existing in the same area, and even in the same cave. It could well be that the two peoples lived side by side in this part of Europe for quite some time.

Who made the findings: Paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak for the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

How teeth helped: The cave, called Grotte Mandrin, has been an archaeological site since the 1990s. Only 9 teeth have been found during that time, with the baby tooth appearing in the same sediment layer as tools made using flint-knapping techniques. This helped them date the tooth and rethink when modern humans arrived in western Europe.

Read more about it: Discovery of ancient baby tooth (or the original research and findings).

5. How women worked and contributed to ancient societies

Here’s a crazy thought: Before 1907, our dentist Dr Lyndsey Browne wouldn’t have been able to practise as a registered dentist in Queensland because she’s a woman. Progress towards workplace equality is an ongoing battle in some (if not most) industries. But evidence from the past suggests societies were more progressive in their thinking towards women and work than some stereotypes would have us believe.

What’s been found: Two separate studies show women holding roles in society previously considered ‘men’s work’. Study number one concluded that women in Ancient Egypt were working as craft specialists, creating high-quality goods. This challenges the notion that only 7 professions were open to women: priestess, musician, singer, dancer, mourner, weaver and midwife.

Study number 2 comes from anthropologists in Britain telling the story of a medieval German woman. By looking at her teeth, they confidently stated that women were working in the publishing industry producing books and manuscripts. Quite a revelation considering how long people thought only males and monks worked on texts from this time.

Who made the findings: Nancy Lovell and Kimberley Palichuk of the University of Alberta made the Ancient Egyptian discovery, while Anita Radini and colleagues discovered women’s contribution to medieval literature.

How teeth helped: An elaborate burial convinced Lovell and Palichuk to spend more time with the business woman from Ancient Egypt. Upon closer inspection, they noticed unusual wear and tear to her teeth. The markings didn’t align with a lifetime of simply chewing food.

By analysing abrasions and the shape of her teeth, they believe she was working with papyrus, running the material through her teeth as she made her wares.

Over in Britain, it was the discovery of lapis lazuli in fossilised dental plaque that caught the attention of researchers. At the time, this material was highly valued as much (if not more so) than gold. Working with it was reserved for the skilled and educated as they created intricate artwork on manuscripts. The amount of blue pigment found in her plaque led Radini and her colleagues to conclude the woman was likely an artist who used her lips to shape the brush.

Read more about it: Archaeologists discover a new profession in an ancient Egyptian woman’s teeth and We found lapis lazuli hidden in ancient teeth – revealing the forgotten role of women in medieval art.

6. Different diets for different genders

Periodontitis (a serious form of gum disease) is higher in adult Australian men than adult Australian women (35% and 26% respectively). Diet and lifestyle habits may play a role in this, but we’re not the first culture to experience gender differences when it comes to oral health.

What’s been found: Men and women living in ancient Sudan had very different diets. They may even have been eating foods that were prepared in different ways (although why it happened is yet to be explained).

Who made the findings: Rebecca Whiting for The British Museum.

How teeth helped: Focusing on remains from ancient Sudan (6,000BC to 1,500AD), Whiting studied the changes in dental and gum disease and noticed differences between male and female remains. The teeth, gums and jaws from the females showed more signs of gum disease, abscesses, tooth loss and dental wear compared to those of the males.

Read more about it: Ancient wisdom: what tooth decay can tell us about the past.

What stories will our teeth tell?

Anthropologists and archaeologists of the future should have an easy time understanding our way of life. We can document and capture the way we live in ways ancient civilisations couldn’t have even dreamed of.

But what if all that was lost? What if the experts of the future had to piece together the past in the same way current historians have done? What might the anthropologist and archaeologists say about the way we lived by looking at our teeth?

Perhaps they’d be interested in how or why we moved from using materials such as gold and silver for fillings to a resin composite.

They may look at our teeth and gums and wonder how modern living affected our oral health. With trends such as fixing gemstones, mouth piercings, and vaping and smoking all changing the condition of teeth, mouths and overall oral health, it’s an interesting one to think about.